I sat down with a fellow PM last week who had just scored a gig as the first Product hire at an established firm. He described the excitement the VP of Engineering showed when he accepted the offer, thrilled to transform a chaotic culture into a “why”-focused organization. My friend was excited to take on this new challenge; what a great opportunity to cut his teeth on leading strategy and developing a Product team and culture. I cautioned him to temper his optimism until he could identify the scope of the organizational change needed to stand up a functioning Product organization. I know - what a downer.

Scope

As mentioned in a previous post, the cost of failing to stand up the Product function compounds over time. A portion of this is simply product debt: we build stuff we shouldn’t because we don’t ask “why.” The challenge of solving this wicked problem is like crack cocaine for Product Managers: for once someone is asking us to analyze what we already have in market. We get to develop a rather greenfield roadmap without the baggage of fitting into existing product processes. To completely trivialize the hard work this requires, it’s like sitting on the floor amidst all our LEGOs, deciding how and why we should put them together in certain ways.

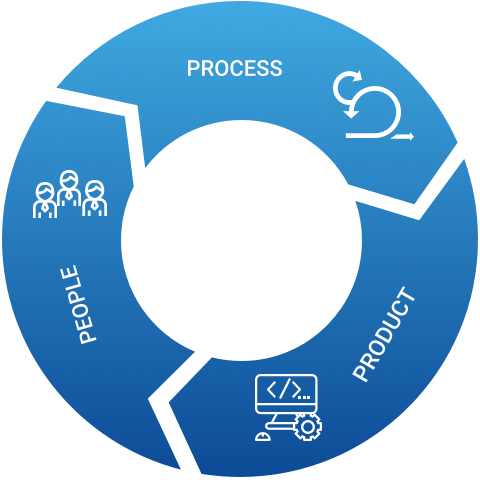

But keep in mind that the job of a Product Manager covers three broad areas: product, process, and people. And it’s the last one that often gets overlooked when standing up the Product function, especially at mature organizations. In the case of my friend, he’s been hired by a champion of change: an advocate and supporter of standing up the product function and the impact this will have on the broader organization. Having this backing is a prerequisite for the change to be successful, but we need a better understanding of the broader organization before we can expect victory. Without this understanding we risk activating another type of change agent: the detractor. And without the awareness of what to expect and from whom, we can set ourselves up for failure when standing up our Product function.

Roles

Readers familiar with the Kotter Change Model will recognize the Champion and Detractor. Both can apply to one or more individuals within an organization at any level of hierarchy or organizational influence. Individuals can become or cease to be either of the roles over time, as well: some people may be won over by effective change (this is the goal!), some may lose faith in the process if change fails to meet expectations.

Concretely:

Champions are individuals who wholeheartedly support and actively promoted the proposed change initiative. They are enthusiastic advocates of the change, demonstrating commitment and belief in its potential benefits. Champions actively engage with others, share the vision, and work diligently to overcome resistance. They often have a deep understanding of the change's purpose and are willing to take on leadership roles to drive its successful implementation.

Detractors are individuals who are resistant to the proposed organizational change. They might be skeptical about the need for change, fearful of the potential negative impacts, or simply uncomfortable. Detractors can be vocal about their opposition, voicing concerns and sometimes even actively working against the change initiative. If their concerns are not addressed effectively, they can become a significant barrier to progress, slowing down or derailing the change process. Their negative attitudes can spread among their peers, creating a culture of resistance and hindering the overall adoption of the new practices.

Any Product person tasked with a key role in organizational change needs to take stock of their champions and detractors before making any change. If we start to bring new ideas, processes, or prioritization methods without knowing who may not adopt them, we risk creating more chaos and solving little. I’ve seen well-supported team transformations torpedoed by a single squad with an engineering manager who insisted on putting non-estimated work in every sprint (!!). The result was unpredictable work delivery that cast enough doubt on the process itself to lose sponsorship. Squads reverted to their previous habits and further change was met with additional skepticism. Without trust our change failed, all because of a single unaddressed detractor.

People

Had this EM’s status as a detractor been highlighted prior to implementation, we could have addressed it in several ways:

Demonstrate early wins with other groups first. Use results to convince the detractor that it has value.

Address the concern directly. Does the EM not like the new process? Do they not see the benefit? Is there a misunderstanding? In short, can we build enough trust to get their support?

Shuffle the team. If we have a champion in a hire/fire position, consider that this person may not be right for the role, needs management training, or similar.

Simply put, change is fragile at its inception. If we recognize the place of people in the equation, suddenly my friend’s job is much larger than simply bringing prioritization techniques to the engineering team. He can come to the table with a solid plan, having considered customer need, engineering capacity and feasibility, value and effort calculations, and a narrative that ties the roadmap together. But without accounting for the shifts teams and individuals will have to make, the plan is not likely to succeed.

I anticipate some readers arguing that because my friend has the support of the engineering leader he will be able to drum up the organizational momentum needed to implement his plan. While the engineering leader is a critical ally, they are not the one who “does the work”. They’re also not the only leader in the organization. It’s impossible to tell from the outside what part the engineering team plays in the broader organization: will other stakeholders be OK with changes in requirements gathering, prioritization, and feature delivery? Will individual Engineers value the opportunity to contribute in the new dimension provided by product? Does this team know how to interact with Product folks, do they need training, do they know why the function is valuable? The engineering leader can help facilitate the investigation but will not be able to conduct it themselves.

Conclusion

Each individual within an organization can and will be a part of the change you’re bringing. We need to keep an eye on how our champions and detractors are trending to ensure our changes will “take”. It’s already a big job to learn, evaluate, and prioritize work that has never been prioritized. The need to focus on people when implementing this change compounds the challenge. That’s not to say it’s not possible: one needs only spend enough time to learn the players and collect the champions prior to announcing any changes. With patience and focus on your people, product transformations are a delightful challenge to tackle. Godspeed.

Sam Gimbel, formerly VP of Product at Clover and co-founder of Clark (acquired 2019), is a product consultant for mid-stage startups. He loves turning detractors into champions.